Evaluating Ventilation Strategies for ICU Isolation Rooms

Sharmista Debnath

This research investigates how common ventilation strategies: laminar flow vs. mixing ventilation, different ACH levels, and negative pressurization ranges affect: Contaminant transport, Airflow patterns, Thermal comfort. The study uses CFD modeling (ANSYS Fluent) to replicate realistic ICU geometry and heat loads under isolated-room conditions.

Abstract

Indoor Air Quality (IAQ) and infection control in healthcare facilities have become a critical priority since the COVID-19 pandemic. These factors plays an important role in patients’ recovery, wellbeing and comfort. This study aims to evaluate airflow patterns and particle dispersion under different ventilations strategies in negatively pressurized isolated ICUs as a case study. The objective is to assess their effect on contamination control and thermal comfort of the patient. For the methodology steady-state Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) is used with Lagrangian particle tracking and Reynold Stress (k- ε) turbulence modelling to accurately represent the turbulence and buoyancy in the airflow using ANSYS FLUENT software. Results demonstrate that laminar air flow systems provide better directional control and efficient contaminant control in the breathing zone, while mixing ventilation achieves uniform thermal stratification under enhanced pressure isolation, making it suitable for high-risk infectious disease scenario. The findings indicate that under both ventilation strategies, a high air change rate (12-20 ACH) and negative pressurization help in effective infection control by reducing the particle clearance times while maintaining patients’ thermal comfort in isolated ICU settings.

Keywords

Ventilation Strategies, Occupant Safety, Thermal Comfort, ICU, Computational Fluid Dynamics

Author

-

Name: Sharmista Debnath

-

LinkedIn: Link

-

Institution: Georgia Institute of Technology

-

Program: M.S. in High Performance Buildings

-

Advisor: Dr. Patrick Kastner, Dr. Paula Gomez

Research Problem

Despite these standards and prior studies, healthcare facilities still face a fundamental design challenge: they must maximize infection control, maintain thermal comfort, and control energy use at the same time. There is no quantitative, ICU‑specific evidence comparing the most commonly used ventilation strategies namely laminar airflow versus mixing ventilation under the same conditions.

Especially with respect to particle clearance times that:

-

how high to push Air change rates,

-

how much negative pressure is beneficial beyond the minimum standard, and

-

how supply temperature and localized drafts affect patients safety and comfort.

Why it matter?

These gaps matter a lot because single wrong choice in ventilation strategy can lead to expensive retrofits, wasted energy, or increased infection risk increasing patients recovery time.

Methodolgy

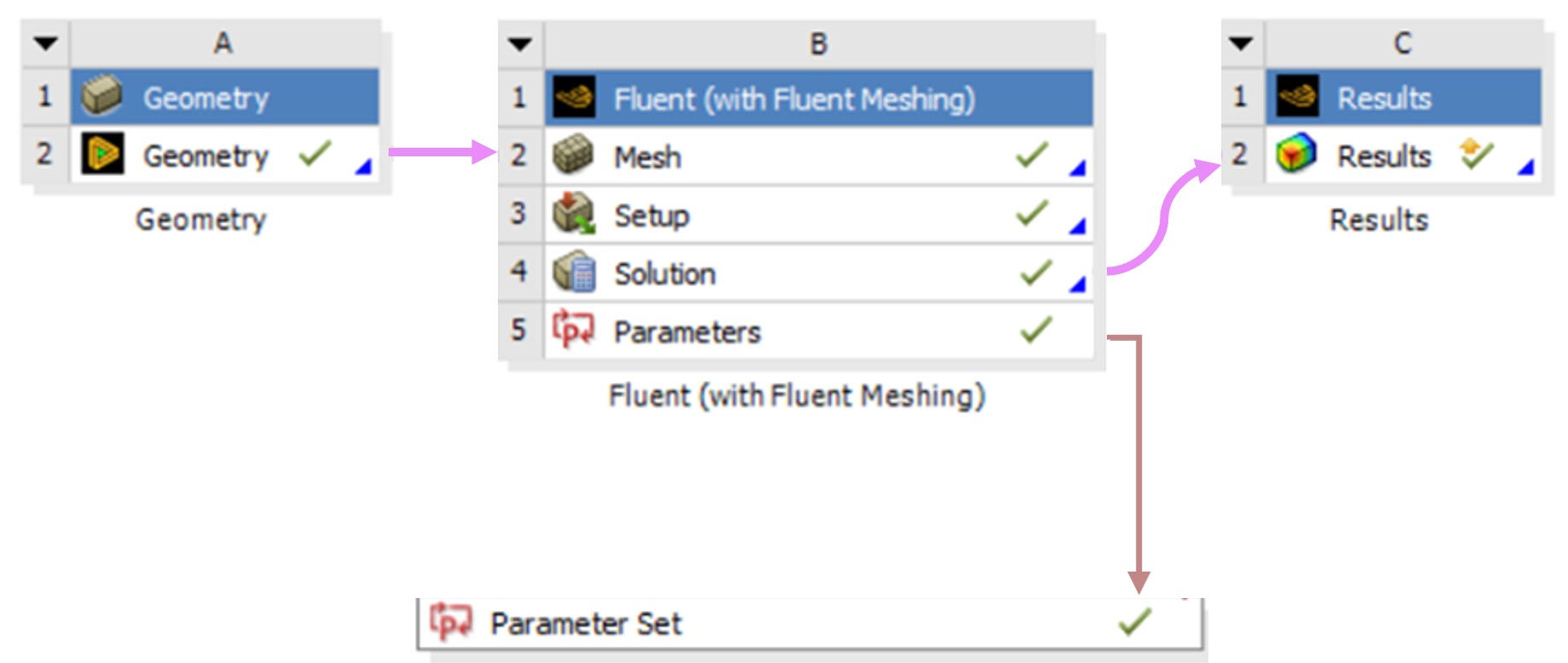

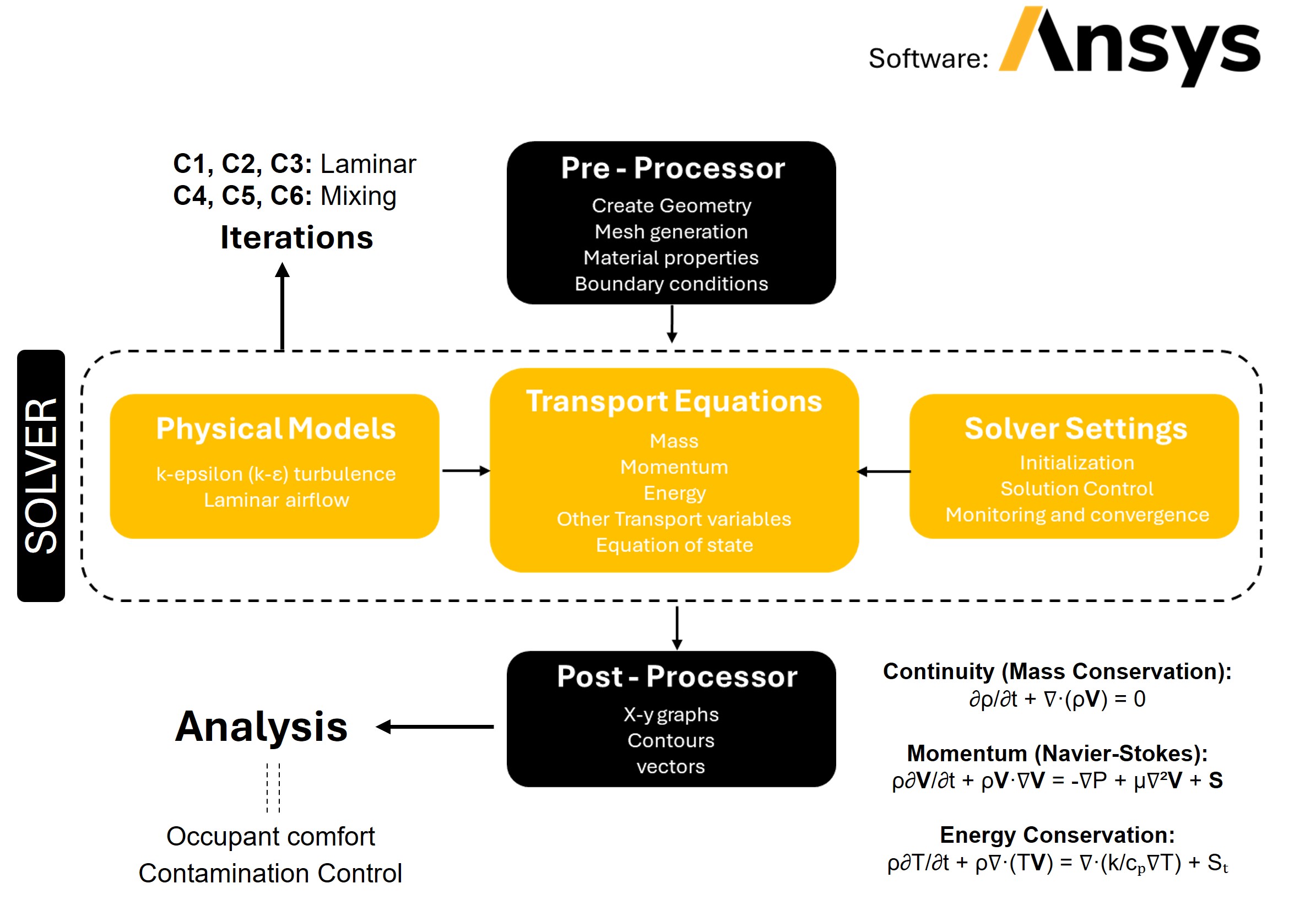

This study uses Computational fluid dynamics to simulate and compare laminar airflow and mixing ventilation in a single ICU isolation room. ANSYS FLUENT, which is a finite volume CFD software, is used for the simulation. The solver uses the continuity equation for mass conservation, the Navier–Stokes equations for momentum, and an energy equation for temperature distribution. A Reynolds‑Averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) approach with a k epsilon turbulence model is applied for the mixing cases, while laminar modeling is used for the LAF cases. Additionally, particle tracking is activated to simulate airborne contamination transport, so that both airflow fields and contaminant behavior can be evaluated consistently under different scenarios. #### The first step is to create the geometry.

This study uses Computational fluid dynamics to simulate and compare laminar airflow and mixing ventilation in a single ICU isolation room. ANSYS FLUENT, which is a finite volume CFD software, is used for the simulation. The solver uses the continuity equation for mass conservation, the Navier–Stokes equations for momentum, and an energy equation for temperature distribution. A Reynolds‑Averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) approach with a k epsilon turbulence model is applied for the mixing cases, while laminar modeling is used for the LAF cases. Additionally, particle tracking is activated to simulate airborne contamination transport, so that both airflow fields and contaminant behavior can be evaluated consistently under different scenarios. #### The first step is to create the geometry.

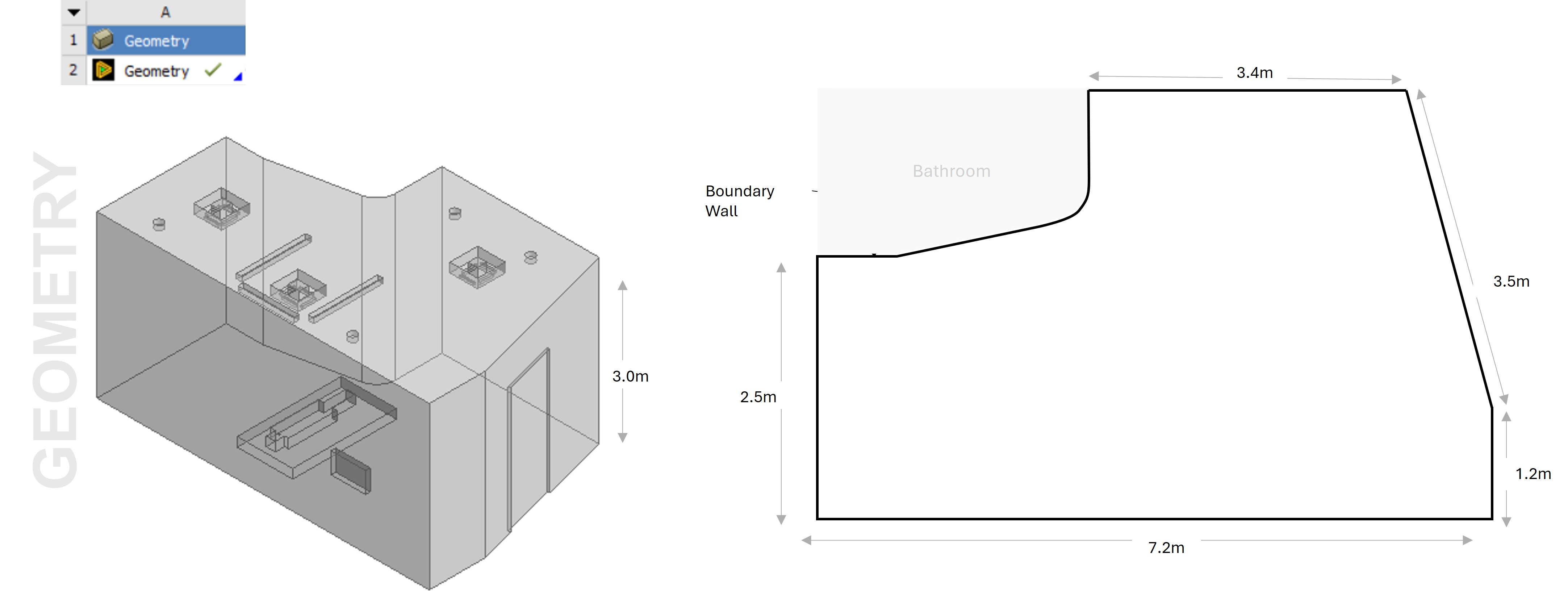

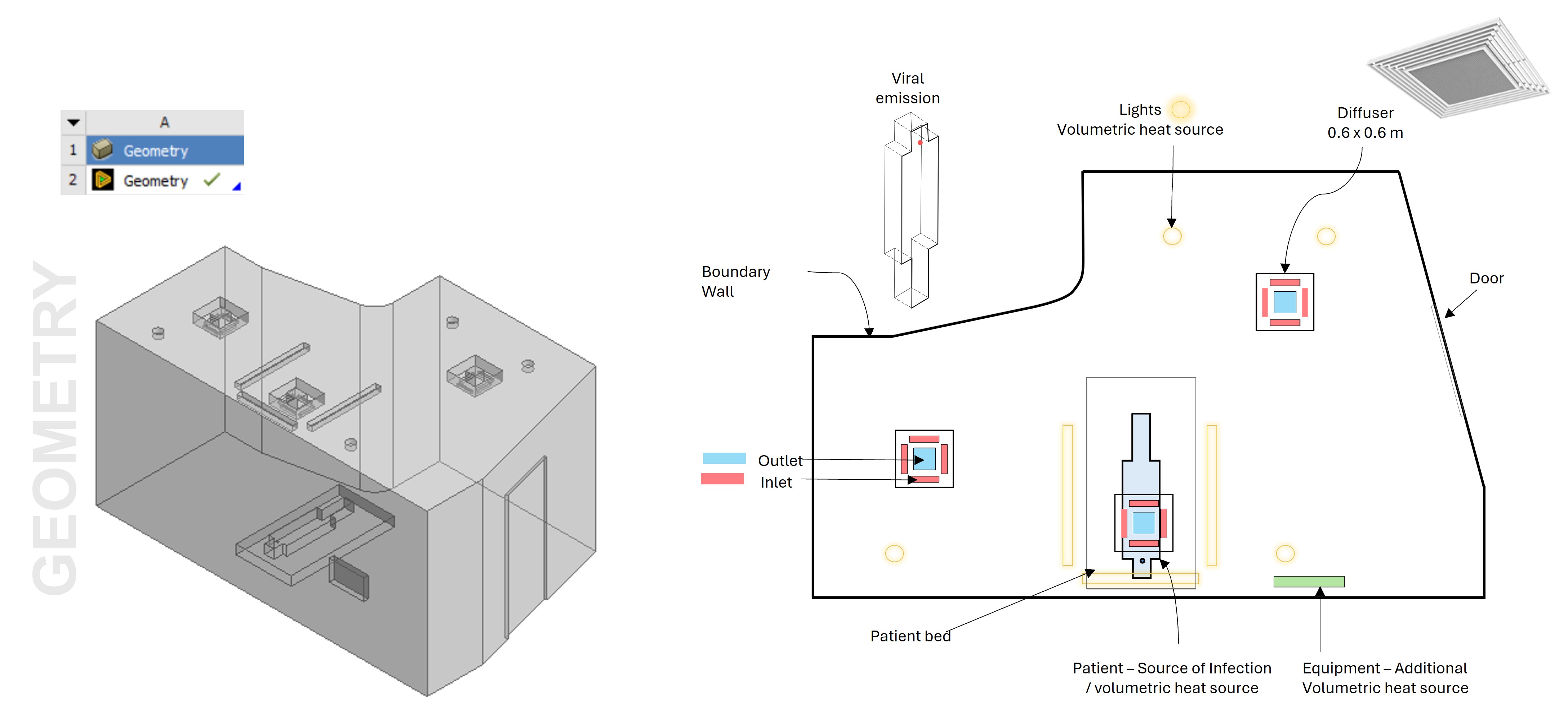

The computational domain represents an actual isolated ICU room, including the main patient area, bathroom (excluded from simulation), supply diffusers, exhaust outlets, lighting, and equipment. The patient is treated as both a source of infection and a volumetric heat source, while equipment and lighting add additional sensible loads. Room dimensions, diffuser sizes, and outlet positions are modeled to accurately replicate the case study layout, and adiabatic no‑slip conditions are applied at the walls. It should be noted that only the convective component of heat transfer is considered, meaning effects such as sweating and radiation are neglected in this first‑order analysis. This simplification allows a clearer focus on how airflow and ventilation strategy influence particle transport and comfort. #### The second step is to generate the mesh.

The computational domain represents an actual isolated ICU room, including the main patient area, bathroom (excluded from simulation), supply diffusers, exhaust outlets, lighting, and equipment. The patient is treated as both a source of infection and a volumetric heat source, while equipment and lighting add additional sensible loads. Room dimensions, diffuser sizes, and outlet positions are modeled to accurately replicate the case study layout, and adiabatic no‑slip conditions are applied at the walls. It should be noted that only the convective component of heat transfer is considered, meaning effects such as sweating and radiation are neglected in this first‑order analysis. This simplification allows a clearer focus on how airflow and ventilation strategy influence particle transport and comfort. #### The second step is to generate the mesh.

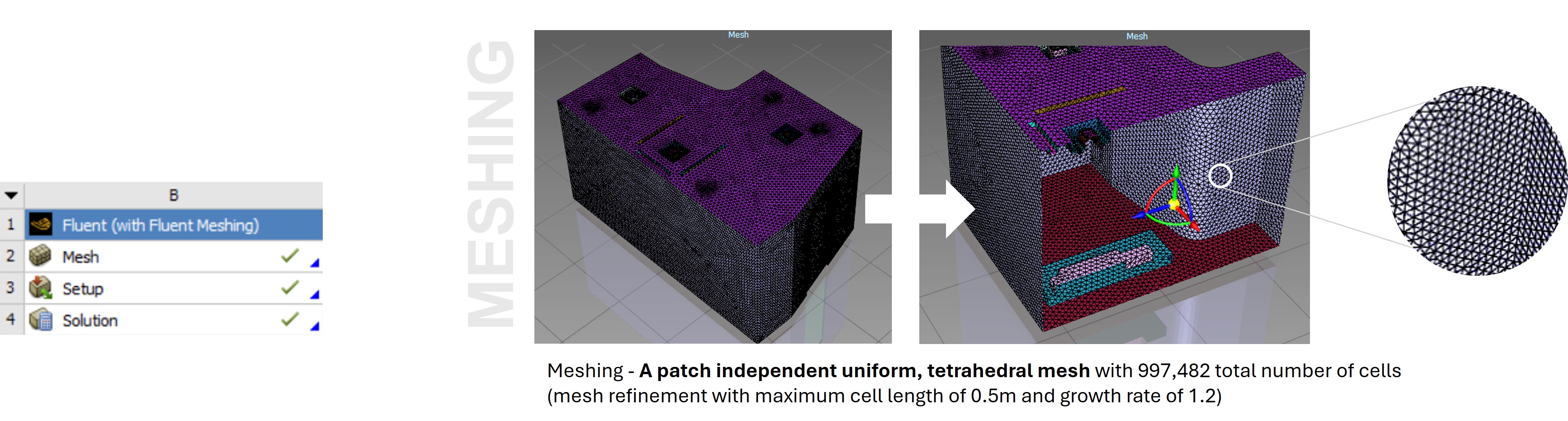

A patch‑independent tetrahedral mesh with just under one million cells is used, with refinement to keep maximum cell length around 0.5 m and a growth rate of about 1.2, ensuring a good balance between accuracy and computational cost. #### The third step is to set-up the solver.

A patch‑independent tetrahedral mesh with just under one million cells is used, with refinement to keep maximum cell length around 0.5 m and a growth rate of about 1.2, ensuring a good balance between accuracy and computational cost. #### The third step is to set-up the solver.

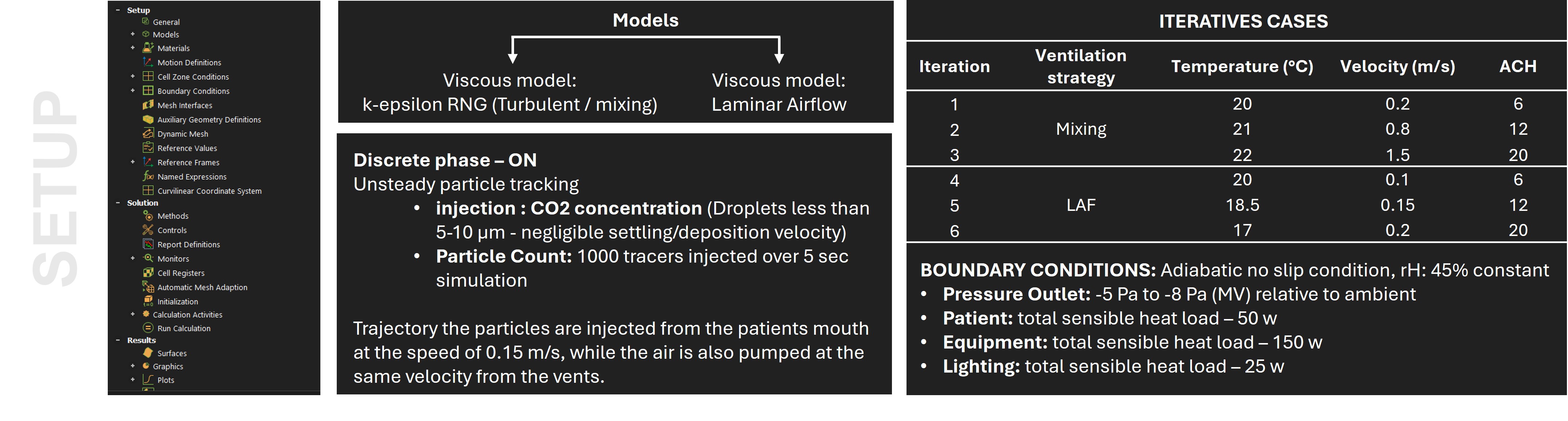

The next step is to setup the solver using a pressure‑based coupled algorithm with appropriate viscous models. Discrete phase modeling with unsteady particle tracking is enabled to simulate the injection of small aerosol tracers representing co2 concentration with neglible settling velocity. Around 1000 particles are injected from the patient’s mouth over a few seconds at 0.15 m/s, while the air is also supplied at controlled velocities. Six iterative cases are defined: three mixing cases and three laminar cases, Pressure outlets are set to represent isolation conditions, with supply and exhaust flows balanced to maintain the desired pressure differential. BOUNDARY CONDITIONS is defined with 45% constant relative humidity. In addition to that total sensible heat load for the Patient, Equipment and Lighting has also been defined. ## Results - The final step is to analyse the results. Using airflow vectors, temperature contours, and particle distributions for the different scenarios. ### In terms of Contamination Control A transient numerical simulation was conducted for a 960 s duration by assuming the initial condition of CO2 concentration level at 1000 ppm, which then would dilute to a background concentration level of 400 ppm. The average CO2 concentration level, temperature, pressure, and air velocity inside the isolation room were chosen to evaluate the performance of the ventilation system and contaminant removal. The results of the airflow distribution pattern from transient simulation over 520 s for each case are presented. The boundary conditions maintain the negative pressure inside the room, the exhaust flow rate is modeled 10% more than the supply flow rate.

The next step is to setup the solver using a pressure‑based coupled algorithm with appropriate viscous models. Discrete phase modeling with unsteady particle tracking is enabled to simulate the injection of small aerosol tracers representing co2 concentration with neglible settling velocity. Around 1000 particles are injected from the patient’s mouth over a few seconds at 0.15 m/s, while the air is also supplied at controlled velocities. Six iterative cases are defined: three mixing cases and three laminar cases, Pressure outlets are set to represent isolation conditions, with supply and exhaust flows balanced to maintain the desired pressure differential. BOUNDARY CONDITIONS is defined with 45% constant relative humidity. In addition to that total sensible heat load for the Patient, Equipment and Lighting has also been defined. ## Results - The final step is to analyse the results. Using airflow vectors, temperature contours, and particle distributions for the different scenarios. ### In terms of Contamination Control A transient numerical simulation was conducted for a 960 s duration by assuming the initial condition of CO2 concentration level at 1000 ppm, which then would dilute to a background concentration level of 400 ppm. The average CO2 concentration level, temperature, pressure, and air velocity inside the isolation room were chosen to evaluate the performance of the ventilation system and contaminant removal. The results of the airflow distribution pattern from transient simulation over 520 s for each case are presented. The boundary conditions maintain the negative pressure inside the room, the exhaust flow rate is modeled 10% more than the supply flow rate.

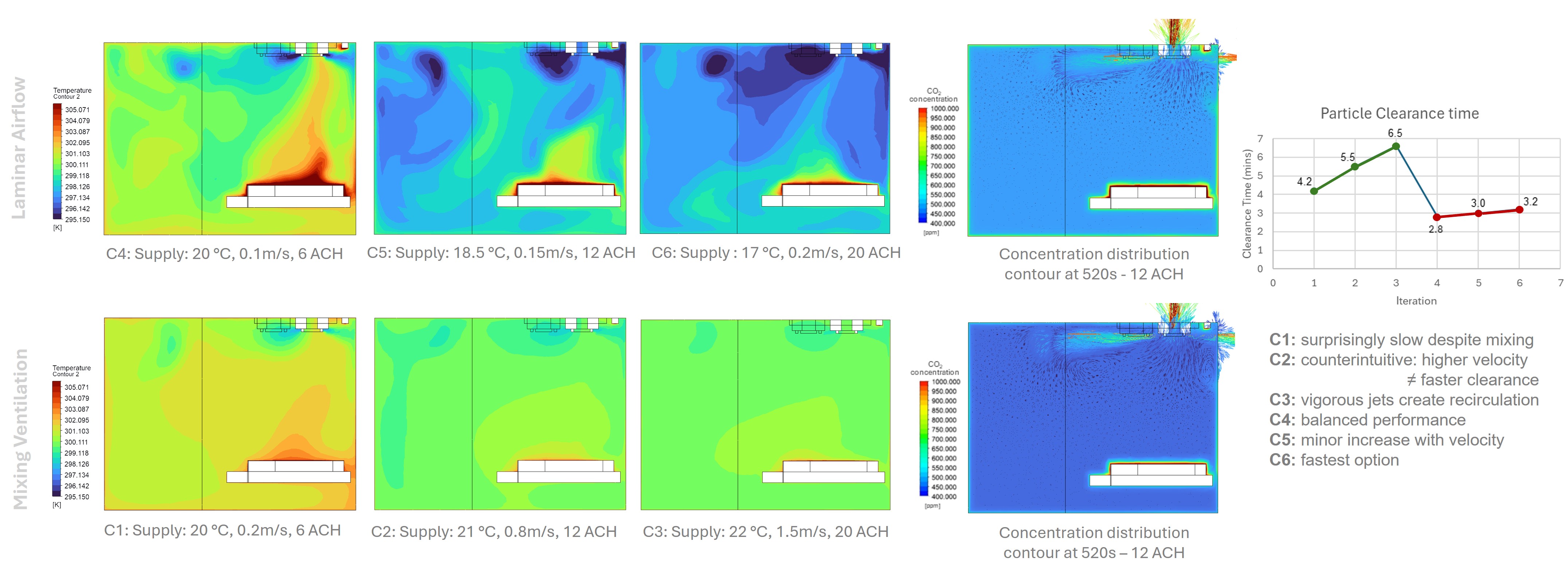

It is observed that Particle behaviour under Laminar airflow has more direct entrainment into descending supply stream with minimal deflection as particles gets concentrated in upper room portion and taking 2.8 to 3.2 minutes for 99% particle removal from breathing zone which is considered 1m from floor level. It is also seen that negative Differential Pressure of 5 pa maintains effective contamination containment While in case of Mixing ventilation Particle Behavior follows a much more Complex trajectory with greater turbulent mixing and recirculation patterns and taking 4.2–6.5 minutes for complete clearance (50% longer than LAF). Additionally, stagnant Zones are formed in the Corners retaining 60–75% of initial source load causing sustained exposure risk. Lastly, pressure differential of negative 8 Pa (enhanced isolation) improves dilution but increases particle residence time ### In terms of Thermal Comfort - #### Laminar Airflow In case of Laminar air flow across all iterations, there is a clear thermal stratification with vertical and horizontal temperature gradients developing throughout the space. In the occupied zone, temperatures remained within 21 to 23.5°C, which is comfortably within ASHRAE 55 and 170 limits.

It is observed that Particle behaviour under Laminar airflow has more direct entrainment into descending supply stream with minimal deflection as particles gets concentrated in upper room portion and taking 2.8 to 3.2 minutes for 99% particle removal from breathing zone which is considered 1m from floor level. It is also seen that negative Differential Pressure of 5 pa maintains effective contamination containment While in case of Mixing ventilation Particle Behavior follows a much more Complex trajectory with greater turbulent mixing and recirculation patterns and taking 4.2–6.5 minutes for complete clearance (50% longer than LAF). Additionally, stagnant Zones are formed in the Corners retaining 60–75% of initial source load causing sustained exposure risk. Lastly, pressure differential of negative 8 Pa (enhanced isolation) improves dilution but increases particle residence time ### In terms of Thermal Comfort - #### Laminar Airflow In case of Laminar air flow across all iterations, there is a clear thermal stratification with vertical and horizontal temperature gradients developing throughout the space. In the occupied zone, temperatures remained within 21 to 23.5°C, which is comfortably within ASHRAE 55 and 170 limits.

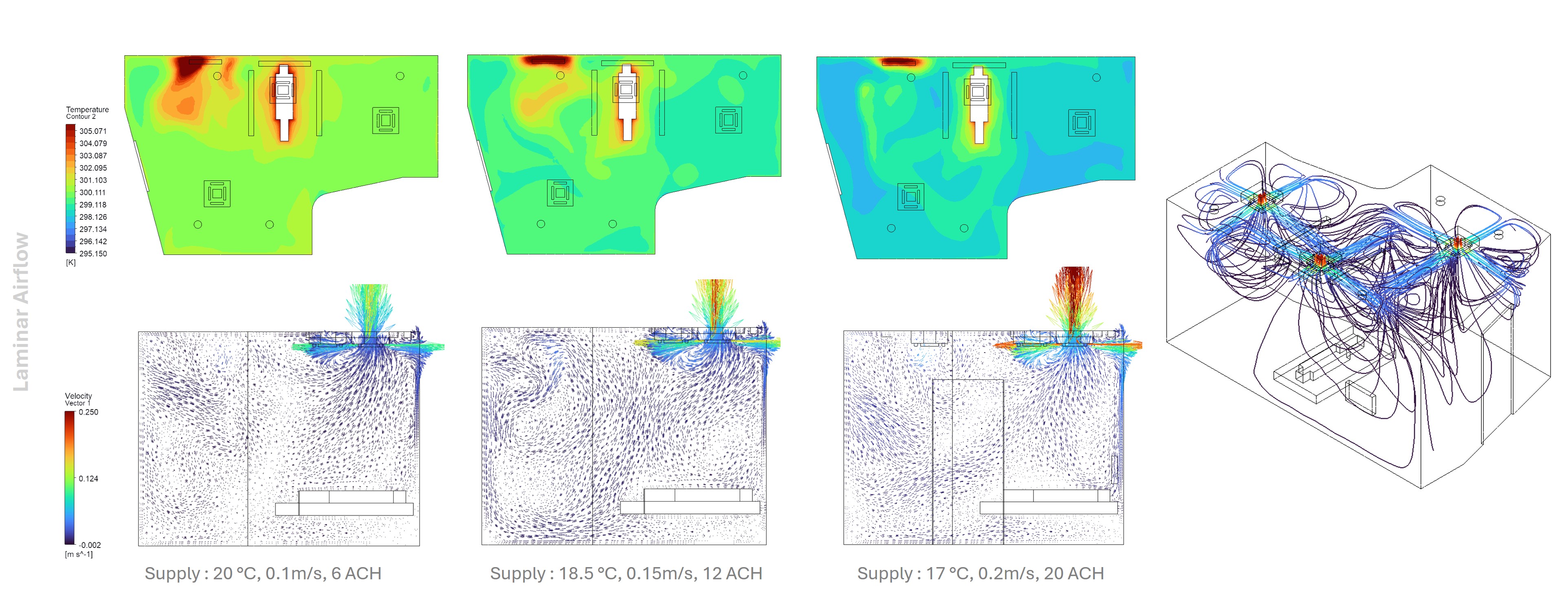

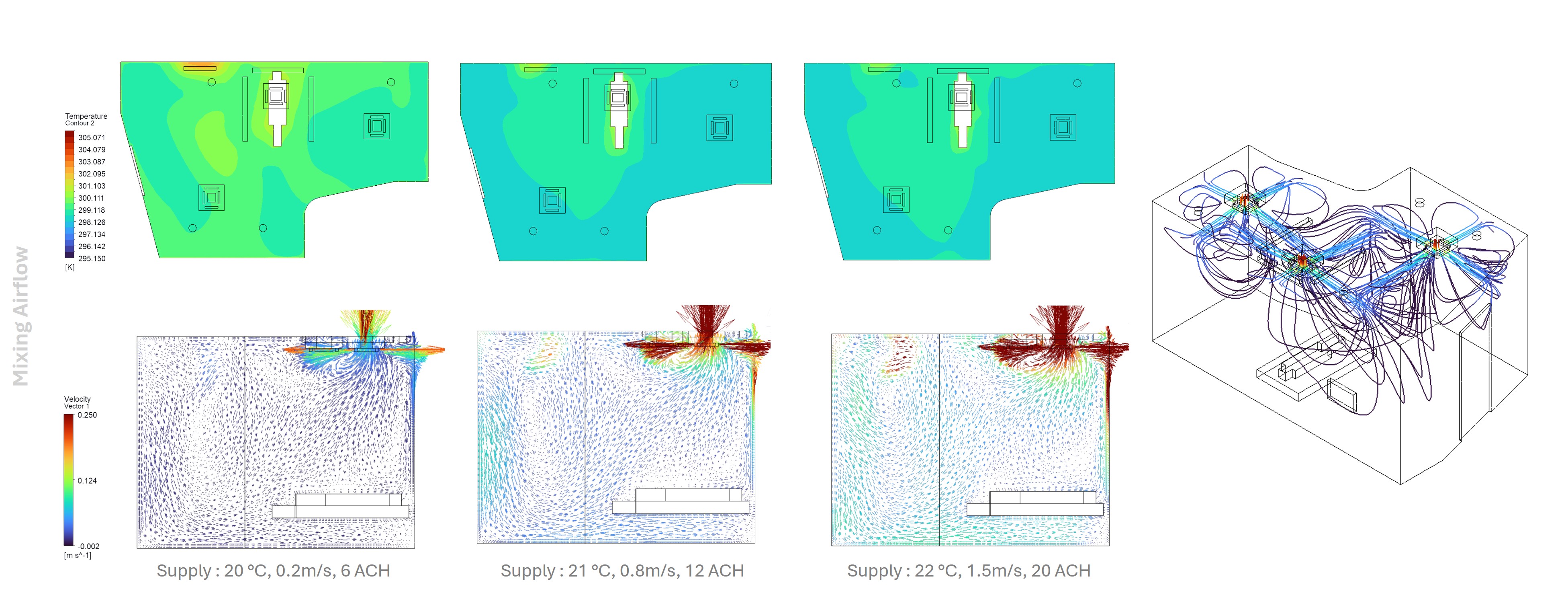

As shown, the cold supply air gradually warms as it absorbs heat from the patient and surrounding equipment. At lower supply velocities, the temperature distribution is more uniform, with only about 0.8°C of vertical variation.At higher velocities, the increased air movement near the supply region resulted in a noticeable temperature drop in the mid-room occupied zone. In the breathing zone, velocities decreased from the supply region in the range of 0.15 to 0.3 m/s, which remains within ASHRAE recommendations for avoiding draft discomfort. Parallel, stable streamlines were maintained in the upper portion of the space throughout all supply conditions. Overall, an airflow rate of 12-20 ACH is seen as the optimal range, balancing efficient contaminant removal with acceptable thermal comfort and minimal draft discomfort. - #### Mixing Ventilation A highly homogeneous temperature distribution across the room volume is observed than the laminar air flow. Thermal stratification was minimal, with only about a 0.5°C vertical gradient. Because of the strong turbulent mixing, thermal uniformity was maintained consistently throughout the occupied zone. The overall temperature range remained very stable, between 22 and 22.8°C, with a nearly identical profile throughout the room.

As shown, the cold supply air gradually warms as it absorbs heat from the patient and surrounding equipment. At lower supply velocities, the temperature distribution is more uniform, with only about 0.8°C of vertical variation.At higher velocities, the increased air movement near the supply region resulted in a noticeable temperature drop in the mid-room occupied zone. In the breathing zone, velocities decreased from the supply region in the range of 0.15 to 0.3 m/s, which remains within ASHRAE recommendations for avoiding draft discomfort. Parallel, stable streamlines were maintained in the upper portion of the space throughout all supply conditions. Overall, an airflow rate of 12-20 ACH is seen as the optimal range, balancing efficient contaminant removal with acceptable thermal comfort and minimal draft discomfort. - #### Mixing Ventilation A highly homogeneous temperature distribution across the room volume is observed than the laminar air flow. Thermal stratification was minimal, with only about a 0.5°C vertical gradient. Because of the strong turbulent mixing, thermal uniformity was maintained consistently throughout the occupied zone. The overall temperature range remained very stable, between 22 and 22.8°C, with a nearly identical profile throughout the room.

As for the velocity, the supply air entering the room generated a strong momentum-driven mixing effect, with high-velocity jet flows forming near the supply diffusers creating multiple eddy formations near corners and boundary regions. - #### Comparison

As for the velocity, the supply air entering the room generated a strong momentum-driven mixing effect, with high-velocity jet flows forming near the supply diffusers creating multiple eddy formations near corners and boundary regions. - #### Comparison

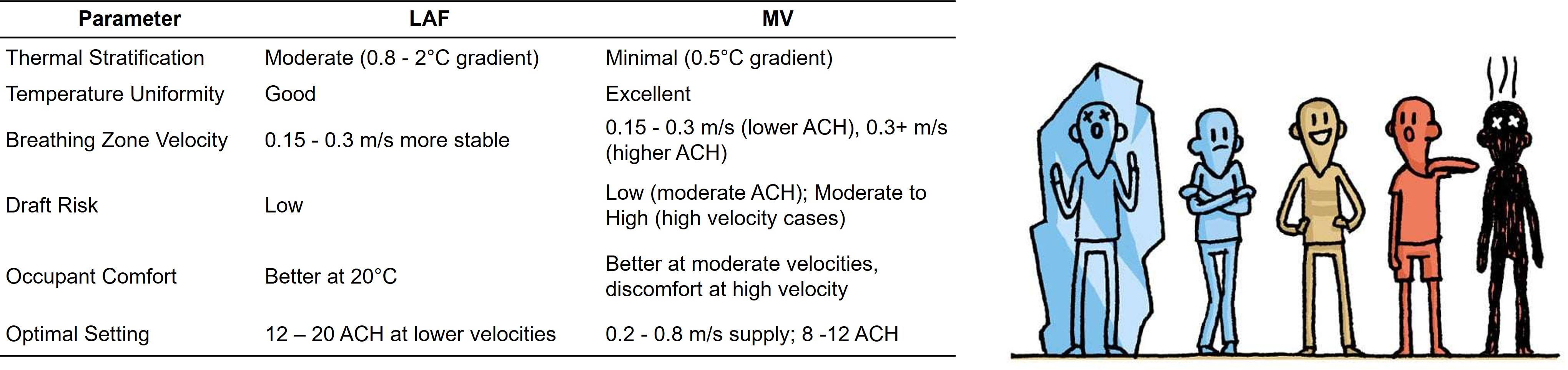

This comparative table summarizes key differences observed in this particular case study. Laminar airflow exhibits moderate thermal stratification but stable breathing‑zone velocities and low draft risk, making comfort performance moderate. Mixing ventilation achieves better temperature uniformity but potential draft at high velocities. From an infection‑control perspective, both systems benefit from a negative differential pressure of negative 5 PA. Yet Laminar provides superior directional control for source containment, while MV relies on more room‑wide dilution. In addition to these thermal and airflow effects, true ICU comfort is multi‑dimensional, so future studies and design guidance should explicitly integrate daylight access and acoustic control alongside temperature, humidity, and air velocity to define patient comfort and recovery more holistically. ## Conclusion This study evaluated different ventilation strategies for a negatively pressurized room to examine their effectiveness. The results illustrated that the contamination control can be improved by increasing the negative differential pressure in the isolated ICU room with respect to the adjacent corridor/ bathroom spaces. Through the moderate negative pressurization, with Laminar air flow demonstrates superior directional control of airflow patterns and effective contamination control in the breathing zone. In case of mixed ventilation, a more consistent temperature gradient is observed making it more suitable for increasing patient’s comfort. The results shows that both strategies perform better at high Air change rates, which also significantly raises the systems annual energy consumption and cost of maintenance. - #### Future Research Future research should examine different adaptive ventilations techniques that combine demand management like CO2-based control, occupancy sensors, and linear reset to automatically adjust ventilation rates based on real-time needs, improving energy efficiency and air quality outside air to maximize the Indoor Environmental Quality and encouraging energy efficiency. ## Source [Link](https://github.com/SustainableUrbanSystemsLab/CS-SharmistaDebnath/) to the repository.

This comparative table summarizes key differences observed in this particular case study. Laminar airflow exhibits moderate thermal stratification but stable breathing‑zone velocities and low draft risk, making comfort performance moderate. Mixing ventilation achieves better temperature uniformity but potential draft at high velocities. From an infection‑control perspective, both systems benefit from a negative differential pressure of negative 5 PA. Yet Laminar provides superior directional control for source containment, while MV relies on more room‑wide dilution. In addition to these thermal and airflow effects, true ICU comfort is multi‑dimensional, so future studies and design guidance should explicitly integrate daylight access and acoustic control alongside temperature, humidity, and air velocity to define patient comfort and recovery more holistically. ## Conclusion This study evaluated different ventilation strategies for a negatively pressurized room to examine their effectiveness. The results illustrated that the contamination control can be improved by increasing the negative differential pressure in the isolated ICU room with respect to the adjacent corridor/ bathroom spaces. Through the moderate negative pressurization, with Laminar air flow demonstrates superior directional control of airflow patterns and effective contamination control in the breathing zone. In case of mixed ventilation, a more consistent temperature gradient is observed making it more suitable for increasing patient’s comfort. The results shows that both strategies perform better at high Air change rates, which also significantly raises the systems annual energy consumption and cost of maintenance. - #### Future Research Future research should examine different adaptive ventilations techniques that combine demand management like CO2-based control, occupancy sensors, and linear reset to automatically adjust ventilation rates based on real-time needs, improving energy efficiency and air quality outside air to maximize the Indoor Environmental Quality and encouraging energy efficiency. ## Source [Link](https://github.com/SustainableUrbanSystemsLab/CS-SharmistaDebnath/) to the repository.